Visitors to Hembury Fort will have noticed a rash of canes and pegs arranged across the interior of the hillfort. These have been set out, in careful alignment with the cardinal points, to provide a grid within which a geophysical survey has been conducted by members of Devon Archaeological Society under the direction of Dr Eileen Wilkes of Bournemouth University.

The survey this spring builds on the evaluation survey that was undertaken by the same team in April last year. This year's work has been more detailed and has been able to cover the whole of the interior of the hillfort thanks to the recent clearance work. All the survey work has been non-intrusive: two techniques have been used - magnetic gradiometry and earth resistance. Results from both surveys are now being processed and the results will inform both the ongoing care and management of the hillfort and interpretations of its use in the past. Excavations at the site in the 1930s and 1980s , by Miss Liddell and Prof Todd respectively, provided evidence that the site had been in use during the Neolithic, Iron Age and Roman periods, with breaks in its occupation between those times. Its advantageous location, with commanding views over the Tale Valley towards the coast, was as useful to people in the past as it is appreciated by visitors to the site today.

Hembury Fort is an Ancient Monument, scheduled and protected in law due to its archaeological significance. A licence to conduct the survey was authorised by Historic England and the work was funded by a grant from Devon County Council. The survey is to be completed as this newsletter goes to press but further information about the previous excavations is available in the Proceedings of the Devon Archaeological Society and details about the current work at Hembury Fort are given on the website at www.hemburyfort.co.uk. This will continue to be updated with news and results.

Dr Eileen Wilkes FSA

Principal Academic in Archaeology, Faculty of Science & Technology, Bournemouth University, Poole, Dorset, UK, BH12 5BB

Members of Devon Archaeological Society conducting the geophysical survey within Hembury Fort (photo: B Welch)

A team of experienced members of Devon Archaeological Society, led by Dr Eileen Wilkes of Bournemouth University, undertook trial geophysical survey within the interior of Hembury in spring 2015. Using both magnetic gradiometry and earth resistance techniques, the team covered areas including those only recently cleared of vegetation to assess whether archaeological features survive in the subsoil. Both techniques worked well and the results suggest areas of archaeological interest in addition to those already sampled by excavation in the 1930s and 1980s.

Further work is proposed and it is hoped that this will reveal more about the past use and occupation of Hembury and assist the positive management of the site.

Dr Eileen Wilkes FSA

Principal Academic in Archaeology, Faculty of Science & Technology, Bournemouth University, Poole, Dorset, UK, BH12 5BB

The following text is taken from the accompanying booklet to the exhibition at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum (RAMM), Exeter in 1935, of objects and other discoveries during the excavations under the direction of Miss Dorothy M. Liddell.

THE excavations at Hembury Fort were carried out from 1930 to 1935 by the Devon Archaeological Exploration Society in union with the Devonshire Association. The work was under the direction of Miss Dorothy M. Liddell, F.S.A. Accounts have been published in the Proceedings of the Devon Archaeological Exploration Society, and a final report will appear in the next part.

The General Committee desires to thank all those who have assisted in the preparation of this exhibition. The Governors of the Royal Albert Memorial Museum for permission to use the Gallery for this purpose and to include material from other sites. Miss Liddell for the arrangement of the exhibition, in which she was assisted by My. T. Shaw. The Curator of the Museum, Dr. R. Churchill Blackie, for assistance and for facilities afforded., To the following for the loan of comparative material and of plans from the sites indicated: Mrs. E. M. Clifford (Notgrove Long Barrow), Dr. E. C. Curwen (Trundle and Whitehawk), Colonel C. D. Drew (Maiden Castle and Jordan Hill), Mr. H. St. George Gray (Cadbury Castle, Glastonbury and Meare Lake Villages),

Mr. D. W. Herdman (Notgrove Long Barrow), Mr. A. ReiHer (Windmill Hill), Mr. E. T. Leeds (Abingdon), Mr. S. Piggott (Holdenhurst Long Barrow), Dr. R. E. M. Wheeler (Maiden Castle) and Dr. E. H. Willock (Haldon).

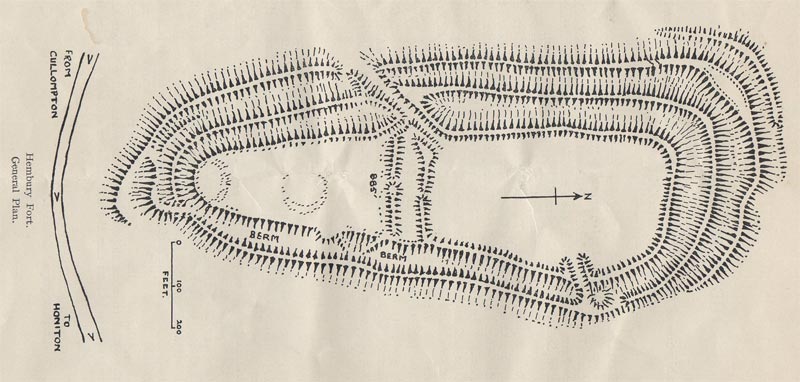

Hembury Fort stands at the end of a spur projecting boldly southward from the main plateau of the Blackdown Hills. It is defended and protected on three sides by steep natural slopes, leaving only a narrow neck of level land on the north. The area enclosed is' about eight acres. The geological formation is greensand, which is in most places capped by clay with flints. There were no surface indications of the neolithic camp. The almost level interior is defended by three valla with intervening ditches, the outer vallum on the east side being destroyed by modern planting. On the north-west a hollow way leading to the plateau is defended by yet a fourth vallum which sweeps round the angle of the Fort. In the centre of the west side and near the north-east corner are entrances which pass obliquely through the banks and ditches. AU these works are now known to belong to the original Iron Age Fort. The interior is divided into two parts by transverse banks and ditches which cross the ridge a little to the south of the western entrance. These are proved to be later than the main defences and belong to a Belgic re-use of the hill fort.

The neolithic settlement was first discovered during the campaign 'of 1931. Since that date parts of a causewayed camp with interrupted ditches have been uncovered at various points.

The Ditches.The principal stretch of interrupted ditch explored is situated in the centre of the hill fort. The western end lies between the two transverse banks. From this area the line runs across the ridge towards the eastern defences of the hill fort. It curves gradually southwards, passing under the transverse bank into the southern part of the camp. Eight lengths of ditch have so far been proved to exist. These vary in length from 25 to 57 feet and are separated by causeways from 2 to 25 feet in width. The ditches average about 12 feet wide and 6 to 7 feet deep. There is evidence that they were not used as pit dwellings, as was found in one of the Sussex camps of this type. The wide, low internal bank has been found in several places with ample traces of habitation on its inner margin.

Another section more than 80 feet long of a silted-up neolithic ditch, together with one of the causeways belonging to this system, was found under the Iron Age roadway leading through the inner ditch up to the eastern entrance.

The Settlement.Traces of neolithic habitation were found in several places. The principal settlement explored lay at the south end of the hill, where a large area was uncovered.

A quantity of daub found shewed that at this point the huts had walls of wattle and daub, or of loose stones with daub roofs, but the form of the huts could not be recovered. Numerous shallow cooking holes measuring up to five feet in diameter were discovered, and by them were clay hearths for heating cooking stones. In some places were shallow depressions containing sherds and thought to have been scooped out to form stands for round-bottomed pots. The large number of objects discovered in this area shewed that the occupation was both intense and prolonged.

A series of small postholes forming the outline of a hut, apparently of circular shape, was found on the margin of the neolithic vallum immediately behind the westernmost section of the neolithic ditch. A cooking hole contained much household debris and an adjacent hearth was covered with splinters of heating stones. The hut possibly formed a guardhouse overlooking a gate at the top of the track way leading up the slope of the hill.

The site of a hut, a pit and other traces of occupation of this period were found on the north side of the western entrance.

Further excavation would be needed to provide sufficient evidence to restore the plan of the neolithic camp. There were at least two lines of interrupted ditch, but their relation to each other is not clear.

The most important finds from the neolithic settlement are the pottery and the implements of flint. Attention may also be drawn to the beads and the grain.

Pottery. (Case 6).Several different neolithic types have been found on the site. The more common have a comparatively coarse paste with much grit of local origin. A rather different group of wares contains grit foreign to the site, which cannot have been obtained nearer than the borders of Dartmoor. The principal form is a round bottomed bowl, with upright or curved sides. Carenated and cordoned vessels occur in the foreign fabrics, together with fairly successful efforts to imitate them in the local ware. Lugs, both simple, pierced and with trumpet shaped ends are included in the series. Decoration is practically non-existent.

The local fabrics belong to the Neolithic (Class A 1) Culture of Wessex, while the imported fabrics are related to another group which is found at many sites on the western side of Britain. Parallels to the lugs and other features of the imported wares may be found in the neolithic pottery of Carn Brea in Cornwall and of the Camp de Chassey and Fort Harrouard in France.

Stone Implements. (Case 1-3).1696 implements of flint and other stone were found in addition to over 16,000 flakes of the same material. The implements include 146 arrowheads of the leaf or lozenge shapes typical of the neolithic period. More sophisticated forms are represented by three barbed and tanged arrowheads, which suggest that the site was still occupied in the early Bronze Age. This is confirmed by the discovery of the tip of a flint sickle,which is also a Bronze Age type. Fragments of 20 ground and polished axes are all of opaque white or grey 'Lincoln flint.' In addition, there are pieces of 15 axes of greenstone of Cornish origin. Rougher implements of chertwere also found, but were less numerous.

Beads. (Case 3).A large bead of jet and a smaller bead of steatite were found in the Neolithic levels. Parallels to these types are quoted from sites attributed to the Bronze Age, but some of them may be earlier. A bead of another type from the Long Barrow at Notgrove is exhibited in Case F.

Grain. (Case 2).About 4.5 ozs. of charred grain were recovered from the neolithic cooking pits at the south end of the site. They belong to a primitive form of the Bread Wheat Race (Triticum vulgare, Host.).

Neolithic A or Windmill Hill is an immigrant culture centred on the chalk lands of Wessex. The typical settlement is a causewayed camp, with one or more rings of interrupted ditches, sometimes used as pit dwellings. The classic example of this form is Windmill Hill, near Avebury, Wiltshire, which has been partly excavated by Mr. A. ReiHer.

The long barrows of Wessex and the analogous chambered barrows of the Cotswold area are collective tombs belonging to this people. In its complete form this culture has been traced as far as Bedfordshire (Maiden Bower, Dunstable), Berkshire (Abingdon), Gloucestershire and Devonshire, but the long barrows and the typical pottery are found as far north as Yorkshire and Northumberland. Hembury is the westernmost example of these camps, but last year a settlement with same culture was discovered by Dr. E. H. Willock on Haldon, near the Belvedere. Further west, a derived form of the same culture is found in the Early Bronze Age villages on Dartmoor, unfortunately not represented in this exhibition.

It has recently been argued that the source of this culture is a continental region in touch with the Swiss Lake villages of the type represented at Cortaillod. In the Rhineland similar causewayed camps are known to have been occupied by the Michelsberg people, but many characteristic finds of that culture are unrepresented on the English sites and it should probably be regarded as a parallel deriving some of its elements from the same source and not as the ancestor of the Neolithic A of Wessex. The later stage of the same culture, known as A, 2 is not represented at Hembury or at Windmill Hill. The pottery is decorated with incised lines and dots. It is found in Sussex and elsewhere in the eastern part of the region and is represented in this exhibition by finds from Abingdon. Further west, in Cornwall and on the coasts of the Irish Sea, a related but distinct form of neolithic pottery is found on habitations sites and in certain types of megalithic burial chamber. Cam Brea, Cornwall, is the nearest of these settlements. The everted rims and the cordoned vessels from Hembury appear to have been influenced by this culture and it is probable that the Devonshire site lying on the periphery on the main Wessex area absorbed elements from its western neighbour.

The large causewayed camps and the great collective tombs prove that these people were settled and that they possessed a considerable degree of organization. They were mainly pastoral, but are known to have cultivated a primitive form of wheat, probably in small enclosed fields or gardens like those found near the slightly later villages on Dartmoor. They lived sometimes in pit dwellings, sometimes in huts of wattle and daub. The rather damper climate of the neolithic period would have promoted a thick growth of forest on the lower and heavier lands, and the settlements are confined to the easily cleared uplands which would have provided ample pasture for their flocks and herds.

No exact date can be given for the duration of this culture. Neolithic B or Peterborough, by which it was replaced on the chalk downs of Wessex, is not known as far west as Devon, and the succeeding Beaker folk can hardly have reached the peninsula before 1700 B.C. Further east, a rather earlier date is indicated and in Wessex neolithic A probably began soon after 2500 B.C. and lasted until about 1800 B.C.

The structure of the hill fort has been explored at several points and the complete plan of the two entrances uncovered. In addition, areas within the banks have been examined to look for traces of contemporary occupation.

The RampartsApart from the actual gateways, sections were cut through the inner vallum at the south end and at the junction with the west end of the southern transverse bank. A section through the inner ditch and the second vallum was cut immediately to the north of the western entrance. The section at the junction of the transverse bank is the more interesting. Under the bank are two old surface lines; the lower of decomposed turf is associated with neolithic pottery and flints, the upper of gritty material, weathered and trampled, curved down to meet a palisade trench. This is covered by the main inner vallum, which in turn is overlaid by the material of the transverse bank. The material of the inner vallum was scraped from the surface, but that of the transverse bank was dug from the corresponding ditch. The palisade trench is U-shaped and about three feet deep It is more or less continuous, with occasional interruptions, the posts being set close together and packed round with rammed stones. The same palisade trench was found at the south end, but here outside the line of the vallum, which was much denuded in this area. A similar palisade trench was found under the centre of the second vallum, and again was proved to have been in position before the construction of the bank. This was composed of a layer of clay and surface chert with a capping of pure greensand dug from the inner ditch. The old turf line was found following the slope of the hill between five and six feet below the summit of the bank. The inner ditch on the north side of the west entrance was thirty feet wide, extending nine feet below the old surface level on the outer side. It is now filled with nearly eight feet of silt.

The West GateThe approach to the West Gate runs obliquely up the slope, passing through the ends of the outer banks and ditches. It then runs between four pairs of enormous post holes which contained whole tree trunks, supporting the reveted ends of the ramparts. The fourth post on each side stands in a double pit with another post carrying the actual gate.

The latter are equidistant from a central post on which the gate probably closed. Within the gate two further pits, each containing a number of large and small posts, narrow the passage to about eight feet and are thought to have carried a bridge by which the defenders might pass from one side of the vallum to the other.

The roadway passing through the entrance is hollowed out to a depth of one or two feet and covered with rough cobbling, which continues for some fifty feet past the barricades into the area of the fort. The palisade trenches on either side may be seen curving round to link up with the ends of the inner vallum. They formed part of the same defensive system and were probably intended as screen for slingers standing on top of the vallum.The great post holes of the entrance were of various sizes up to 7.5 feet deep and 4.5 feet in diameter. Within these were set the great posts, which measured up to 2t feet in diameter; and were packed round with rammed stones. Traces of timber found at the base of some of the holes were of oak.

The East GateThe east entrance was similar to that described above, except that there were no revetment posts and the palisades met each other without turning inwards. It was found in the course of the excavation that the roadway leading up to the gate passed across the end of one of the silted up neolithic ditches. The cobbled causeway extends 70 feet from the gate to reinforce the road over this soft ditch filling.

OccupationSearch was made in several places for evidence of an occupation contemporary with the main defence of the hill fort. The only structural evidence uncovered was a hut at the foot of the eastern vallum about halfway between the entrance and the transverse banks.

The pottery contemporary with this hill fort has a fine paste, dark or reddish grey. The sides of the vessels are fairly thick and they are mostly ornamented with incised pattern. This class of pottery is typical of the Lake villages of Meare and Glastonbury. At the former it is associated with a brooch of La Tene I type, probably of the third century B.C., but the latter belongs principally to the first century B.C. and the succeeding generation. In Devon and Cornwall this pottery is commonly found on Iron Age sites, and in Cornwall it continued in use at least as late as A.D. 100.

Metal. (Case 5).Metal was very scarce on the site. The iron shoe of one of the revetment posts is exhibited and a few other unimportant objects of bronze and iron were found.

Beads. (Case 5).Parts of two glass beads are recorded. One of these has an inlaid band of yellow, brown and white. Similar beads are recorded from the Lake villages.

Sling Stones. (Case 5).Over 3,000 sling stones were found on the site, including several hoards, some of more than fifty. The pebbles weighed about 2 ozs. and were all of material easily procured within a short distance of the site. They were not found in or under the encircling banks, but frequently occurred in the make-up of the transverse banks, showing that they were in use during the occupation of the great hill fort. In no case were they associated with the neolithic occupation.

The Iron Age in southern England is generally divided into three parts, A, B and C, which are not necessarily successive in every district. The great hill fort at Hembury belongs to the second phase and the Belgic alterations to the third, but in order to understand their place in the prehistory of the period it is necessary to glance at the earlier events.

Iron Age is represented at various places on the south and east coasts of Britain and penetrated deeply inland from these points. One variety of this culture, characterized by the use of sharply carenated bowls of red haematite ware, is widely spread in Hampshire and Wiltshire. It is often known after the site at All Cannings Cross, which was exhaustively explored before and after the War. The people responsible for this culture are related to the inhabitants dwelling in the Marne Valley and other parts of northern France in the sixth and early fifth centuries B.C. In Britain several sites have yielded bronzes suggesting a rather later date. All Cannings Cross is attributed to A 1, but as the culture spread inland it assumes a more debased form, known as A 2. In this later phase the people began to erect hill forts. The earliest defences on Maiden Castle are their work and are attributed to about 400 B.C.!

During the latter part of the period, when the A people were in control of south central England, another group of invaders had landed in Devon and Cornwall. Though probably related to the early people, they are characterized by a different culture known as B or Glastonbury. This is best represented in the famous Lake villages of Glastonbury and Meare, but typical pottery has been found in nearly everyhill fort in Devon, Cornwall and Somerset where excavation has taken place. This people are responsible for the great hill fort at Hembury, which they occupied as an uninhabited site, which had remained deserted since the end of the Neolithic village more than 1,500 years earlier. The beginning of the site should probably be placed during the first or second century B.C. At Maiden Castle the stupendous re-fortification of about 100 B.C. is probably due to these people. Their expansion has been connected with the metal trade and the pottery and other objects from the south-west are evidence of a connection with Brittany and north-west Spain and Portugal. Since in the west the culture survived into the Roman period, there is no reason to doubt their identity with the Dumnonii who historical writers locate in this peninsula. Further east their territories were curtailed by the advance of the Belgae at the end of the first century B.C. and the beginning of the first century A.D.

The only structural features attributable to this phase are the transverse banks and ditches and a single hut. The southern bank runs on to the inner vallum immediately behind the secondary entrance and blocks it entirely. Similarly, the end of the northern bank runs on to the surface of the earlier roadway blocking the main western entrance. This end is reveted with a kerb of chert boulders. The banks are comparatively slight with V-shaped ditches on the southern side. Near the centre of the south bank is an S-shaped entrance protected by an overlap of the ends of the bank and ditch and blocked by a wooden gate. It is certain that much of the earlier defences remained in use at this phase, which followed immediately on the earlier Iron Age occupation. The eastern gate apparently remained in use as the main entrance to the earthwork, but the purpose of the alterations to the west gate is not clear.

The most important find of this period is a small group of pottery found in the silt of the southern transverse ditch. This includes a carenated bowl, a bead rim bowl and a wheel turned olla of pre-Flavian type (i.e. not later than A.D. 60). The bowl, which is decorated with raised ribs and studs, is probably copied from a metal original. It belongs to a class of pottery found in the earliest deposits at Exeter and several sites in Dorset. Similar pottery, associated with Samian and other early Roman wares, was found in the contemporary hut.

The first century B.C. and the following fifty years saw the south and southeast of Britain invaded by two waves of Belgic peoples from the Low Countries and northern France. With the first which occupied Rent and the basin of the Lower Thames between 100 and 50 B.C., we are not concerned.

The second invasion began after 50 B.C. and occupied south central England. It is characterized by wheel-made bead-rim pots, which are found in great number. A related culture is recognized in Dorset with carenated bowls sometimes decorated with vertical ribs and bosses. This people occupied Maiden Castle in the last generation before the Roman Conquest of A.D. 41 and occupied Hembury at a still later date, probably only a few years before the Conquest. Their exact place of origin is not yet located, but wares similar to the bead rim vessels occur over a large area in north-east France. In England their identity with the historical Belgae who occupied Winchester, Bath and probably Ilchester, is not open to doubt. Similar pottery survives up to and after the Roman Conquest, when it is absorbed in the general Romanized culture of the province.